| technic |

| artists |

| links |

| material |

| contact |

| home | bibliography | scannotique |

| exhibitions |

![]()

Josie Iselin

Pregnant

Birth

Shoes

Pantry row

Leaves

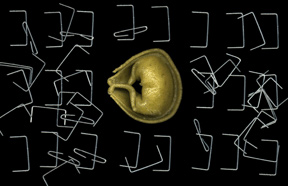

Opercula

Bali Spread

Stones

| Who is Josie Iselin | ||

She uses her flatbed scanner and computer exclusively for generating her imagery. She has done so for over a decade and is still captivated by the fluidity with which this technique allows her to render and design with three-dimensional objects. Each book is built with-in the computer, in essence as a piece of sculpture. Her first book, Loving Blind/SeeingRed: A Mother’s Decade, was produced as an artist’s book by Trillium Press, Brisbane, CA in 2004. Her second and third books, Beach Stones and Leaves & Pods, were both released in 2006 by Abrams, an imprint of Harry N. Abrams, Inc, New York, NY. Her third book in the series on forms in nature, Seashells, came out in June 2007 and the fourth book, Heart Stones, is launching in time for Valentines Day, 2008. Josie has three children. She was the president of her children's elementary school PTA and helped develop and implement a parent-funded arts program which has become a model within the SF Unified School District. Her husband, Ken Pearce, works for an independent motion-capture and animation studio. They live on a steep hill in San Francisco. All Images Copyright See more of Josie's creations

ARTIST'S NOTE: As every photographer knows, the ordinary is anything but. For years I have mined my household for everyday things and used my flatbed scanner to examine them: dryer lint, vegetables, balls of yarn, even the collections of stones piled around the house, which gave rise to the first book in this series, Beach Stones. When I found a perfect skeleton of a lemon leaf in my backyard compost bin—the scanner captured it in all its delicate, decomposing glory—I was inspired to venture into the neighborhood and to the botanical garden to look particularly at leaves and pods.

The first leaf images to emerge from the scanner on to my computer screen startled me with the intensity of their color and form. After working for months with the subtle variations and muted hues of softly silhouetted beach stones, I was delighted by the sharp visual detail each leaf provided: the distinct shapes; the intricacies of the vein systems; the range of brilliant, saturated color; the crisply smooth or spiny edges. Learning the purpose those attributes serve in sustaining both the tree and life on our planet has been thrilling. My use of a scanner instead of a camera is well suited to exploring forms in nature such as leaves and pods. The focus of scanner photography is strictly on the object, and it allows for a fantastic clarity as I zoom in closer and closer. It follows in the tradition of Karl Blossfeldt, who built his own large-format camera in 1896 to make stupendously graphic images of plants, and expands on the concept of the photogram, an image made by setting an object directly on the exposing photopaper. The scanner’s flat glass surface is a fluid conduit for rendering three-dimensional objects into two-dimensional artwork and lets me design quickly. Timing is important: I had only hours—or at most a day or two—before the leaves began to deteriorate. I even devised a traveling studio with my laptop and scanner to capture them on the road. Although, on close examination, each detail of leaf and pod seems like an exotic revelation, most of the ones shown here are relatively common. They come from the trees in my San Francisco neighborhood or in friends’ backyards, from Boggy Meadow Farm in New Hampshire (thank you, Lovell-Smiths) and from Sky Farm in Maine (thank you, Lamonts). Many come from two fantastic horticultural realms, the San Francisco Botanical Garden and the Brooklyn Botanic Garden. This project has been a collaboration with Mary Ellen Hannibal and many others. I must thank Jackie Fazio and Leeanne Lavin at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden for guiding me through their collection. I also thank Eric Himmel, editor-in-chief of Abrams, for setting me on this exploration of forms in nature; Caroline Herter of Herter Studio for connecting us; Kate Stickley for numerous plant identifications; Cathy Iselin, a constant inspiration and help; and Mike Sullivan for writing a wonderful book, The Trees of San Francisco, that led me to the most interesting trees in my hometown. The Abrams team—Darilyn Carnes, Nancy Cohen, and Jane Searle—is a privilege to work with. Last, I thank my husband, Ken Pearce, and my three children, Eliza, Deedee, and Andrew. Their delight in my projects inspires me, and their advice almost always results in something better.

|

||

Fava Beans

Red cabbage with leaf